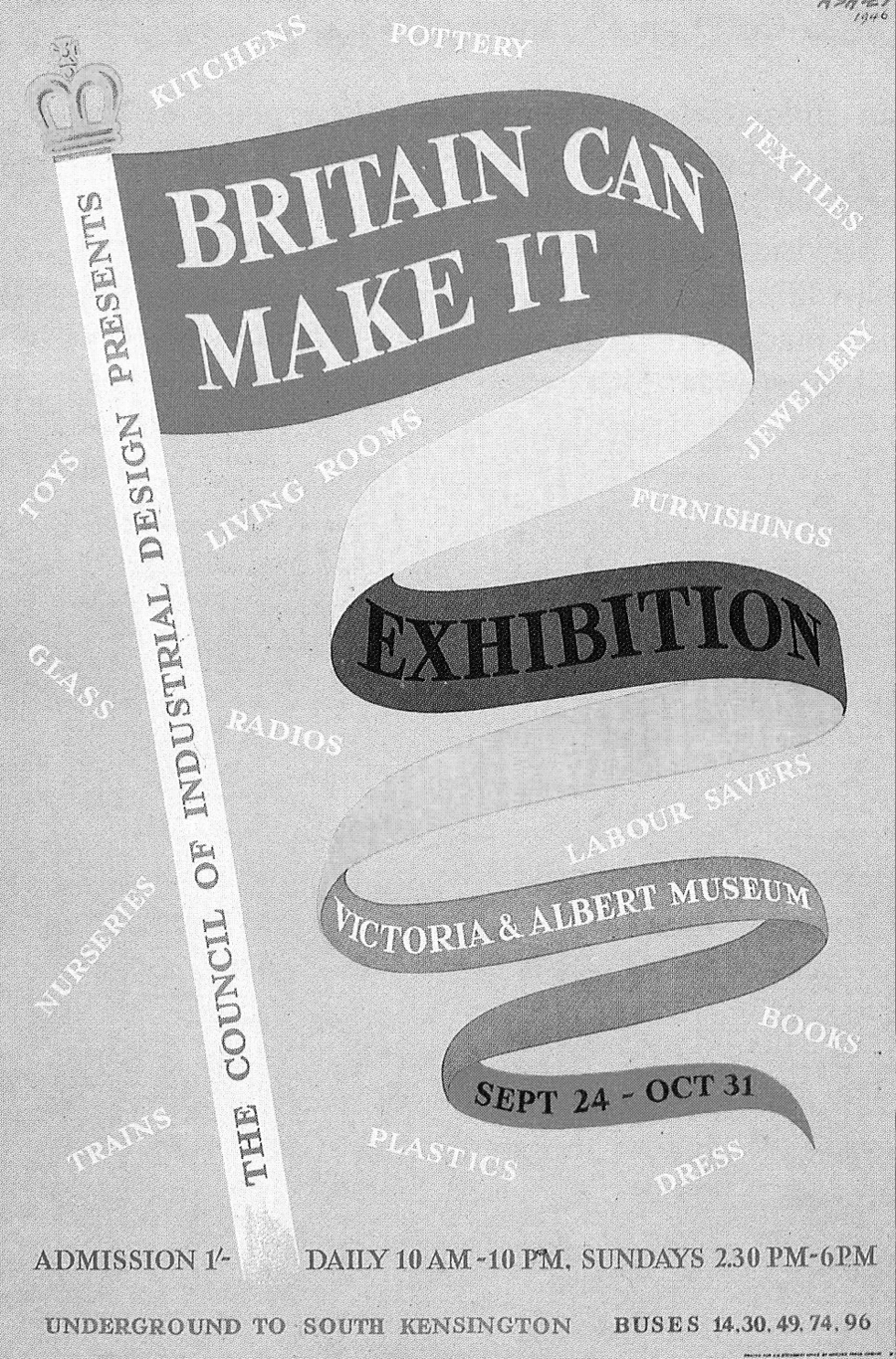

On the last weekend of September 1946, London families are flocking to the Victoria and Albert Museum to see the Britain can make it exhibition, organized by the newly created Council of Industrial Design. The country is victorious but in ruins, having paid a high human and material cost during the war; daily privations and restrictions are still harsh. Luckily the exhibition’s sections, with names like War to Peace and What Industrial Design Means, promise a bright future – the war effort is being transcended by technological progress and its corollary: the hope of a better life. This élan is thanks to Britain’s proud industry, which adapted its operations to the circumstances of the war thanks to an emergency plan established by the State.

For now, this production still has the bitter taste of restrictions, as the population knows only too well the CC41 logo, standing for “Controlled Commodity, 1941”. Reginald Shipp designed the logo at the request of the Chamber of Commerce, and the Britons have dubbed it “the cheeses”. It is imposed on all items of clothing, furniture and manufactured goods made by domestic companies participating in the war effort. Not a sock is spared. This remarkable logo embodies perfectly State-controlled production, distribution and consumption, and thus tells a hardly liberal story of the British economy.

The Second World War Utility Scheme is an industry rationalization program created by the British Chamber of Commerce in 1941 and fully implemented in 1943. It is run by an advisory committee, which sets a small number of authorized models of clothing or household items to be produced by a closed list of companies, while all others are enlisted to produce weaponry. It is an authoritarian but efficient method of managing raw materials and resources, so that domestic industry participates in the war effort. The State also organizes distribution, through coupons for so-called Utility Products. Rationing applies mainly to food and clothing, but some coupons are for furniture. These are distributed primarily to newlyweds settling in, to families who have lost their possessions in a bombing or to pregnant women as they prepare for a new baby.

Utility living room © Courtesy of Design Council/DHRC, University of Brighton

“The function of the (…) committee (…) will be to produce specifications for furniture of good, sound construction in simple but agreeable designs for sale at reasonable price, and ensuring the maximum economy of raw materials and labour." (1)

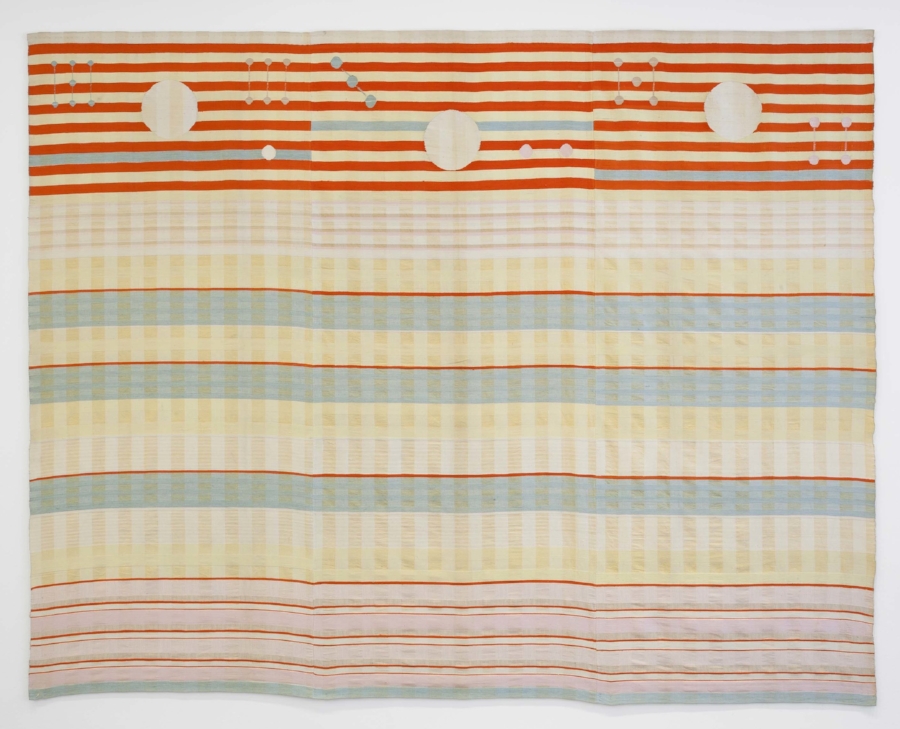

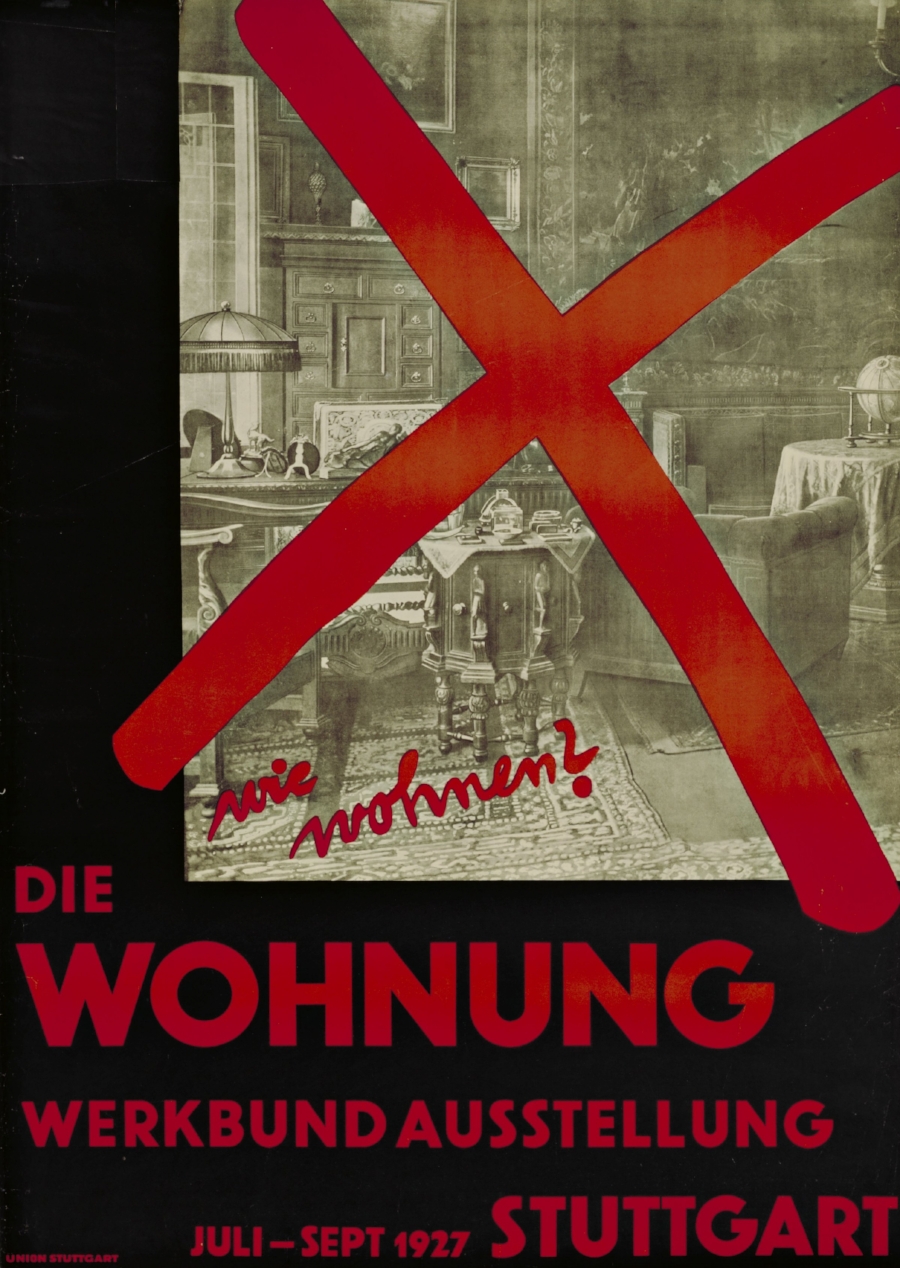

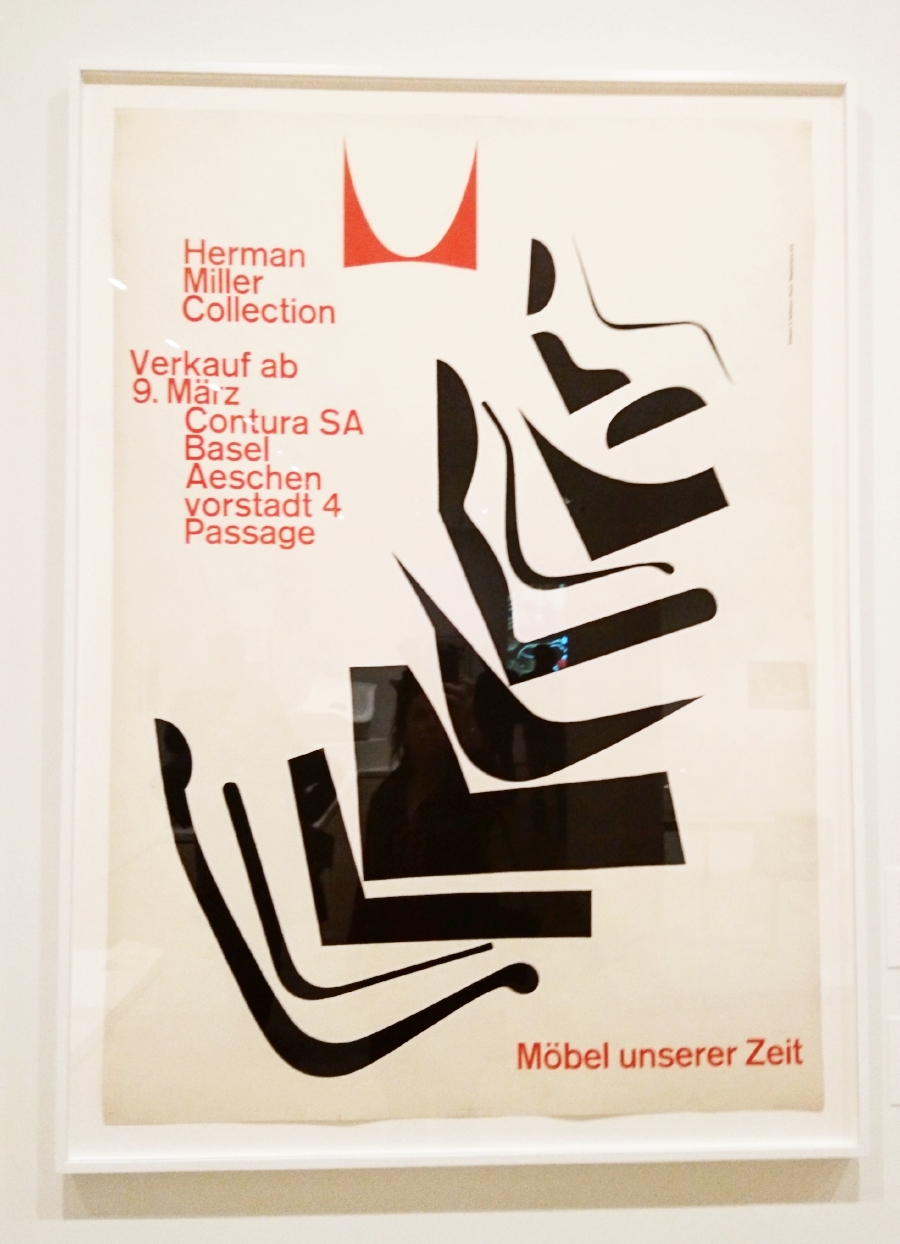

Though the period is short (the plan runs until 1948 and is definitively abandoned in 1952), it is pivotal in the history of British design. Ever since William Morris harshly criticized the misdeeds of mass production at the end of the 19th century, nothing much had changed in household goods: in 1937 the German art critic and historian Nikolaus Pevsner, freshly exiled to the UK, wrote in An Enquiry into Industrial Art in England (2) that the industry was guilty of imposing ugly, over-decorated, substandard furniture on the nation. The urgent need for broad access to simple, good-quality household items crystallizes in the war effort’s authoritarian rule, while making irrelevant any debates on standardization of interiors. It underlines the need to reform design, replaces the designer at the heart of the process of manufacturing, and asks what a democratic and honest design should be; this is how “good design” and the accompanying debates come about. This idea instills dynamism in British furniture design that lasts well into the 1960s.

Victorian bedroom vs Utility bedroom, 1943 © Courtesy of Design Council/DHRC, University of Brighton.

When the country goes to war in 1939, the Chamber of Commerce needs to make up for the shortage of raw materials on the isles, since the usual commercial routes are cut off. In particular, the import of wood from North America, Russia and the Baltic countries is compromised, putting furniture manufacturers at risk. The Chamber needs to help ailing companies in maintaining a reasonable product range, so in 1939 Timber Control is created, a wood industry supervision body managing raw materials and imposing set prices on suppliers. But the results are disastrous: Furniture manufacturers only use the wood for some traditional, luxurious and expensive pieces, and use bad quality imitation wood to produce cheaper items. It soon becomes clear that neither price restrictions nor controls on distribution can ensure popular access to quality goods. So in 1942, citing the war effort, the Chamber decides to impose a limited number of furniture models, whose design fits with the urgent need to save raw materials, and the process dictates rationalization of manufacturing. The authorities also decide to hire their own designers, to ensure the goods are equitably distributed, and that in these hard times the poor, too, can furnish their homes. It is no secret that for the committee, the economic and social benefits of the plan will be rounded off by the educational and cultural virtues of a crash course in Modernist good taste:

“Both the manufacturers and the public will have to be educated away from the "frills and fancies" of the present commercial products towards articles which through simple and even "austere" in design are far more serviceable, practical, hard-wearing and pleasing for the eye. Here seems an opportunity which should not be missed for designers and craftsmen to co-operate through the exigencies of War to make a contribution towards the general betterment of furniture design and construction." (3)

It is time for Britain to bid farewell to the bad taste inherited from Victorian times, and to explore the joys of interiors as modern as they are austere. The committee readily admits that the latter may be a questionable esthetic value, but is it not a better fit with these dark times? Twenty years later, Gordon Russell, a designer and member of the Utility Scheme’s advisory committee, speaks of this war on ornamentation in his autobiography:

“With the introduction of Utility furniture, the basic rightness of contemporary design won the day, for there wasn’t enough timber for bulbous legs or enough labour for even the cheapest carving and straightforward, commonsense lines were both efficient and economical." (4)

In this way the advisory body takes total control of the furniture industry, from the design of pieces up to the consumer’s choices: In August 1942 the committee, presided over by a reformist manufacturer, Charles Tennyson, approves designs by Edwin Clinch and Herbert Cutler. In September the prototypes are presented to the public. In March 1943 the committee selects 132 companies, divided into 38 manufacturing zones; different models of furniture are assigned to the companies according to their machinery and know-how, and the standardization of production is carefully controlled.

Thus the government imposes a new system of consumer goods manufacturing, promoting local use: motor fuel is scarce, so distribution must be close to the manufacturing site. And so at any retailer, any British family can consult the single Utility Furniture catalogue listing some 30 items, from kitchen chairs to cradles.

Page du catalogue Utility Furniture © Courtesy of Design Council/DHRC, University of Brighton.

Even though this restructuring of the furniture market allows some companies to survive and even to prosper, it provokes certain hostility from the sector’s professionals, who have lost control over their production, and particularly over the design of their products. They feel dispossessed of their know-how, and retailers, upset with the imposed esthetic revolution, echo those complaints. Some mourn the passing of shimmery French polish, replaced by a cheaper matte polish of unexciting sobriety. The opinion of the consumers themselves is hard to ascertain. An opinion poll in 1945 shows that housewives owning CC41 furniture are quite satisfied with their purchases – especially if compared to their assessments of wartime clothing, which the population quite strongly rejects. It is most probable though that in times of necessity, esthetic considerations do not count for much.

And what about the plan to acquaint the public with the virtues of Modernist design, to cure the flawed preference for traditional frilly ornaments? Even if the idea is horribly pretentious, the Utility Scheme undoubtedly introduced, by fair means or foul, somber furniture into British interiors, and that furniture later even had a “vintage” appeal. It could even be credited with updating a certain vernacular esthetic, and giving center stage to domestic designers. And finally, in the context of today’s growing discussions of depletion of natural resources, it gives an unequivocal and captivating lesson on State-imposed reduction and control of consumer goods. After all, isn’t Utility Scheme, with its local management of resources and know-how, the ancestor of slow design?

Translation by Wanda Gadomska

(1) Board of Trade, 8 July 1942, cited in Geffrye Museum, Utility Furniture and Fashion 1941-1951, London, 1974, p.12.

(2) Nikolaus Pevsner, An Enquiry into Industrial Art in England, Cambridge, 1937.

(3) Memorandum from O.H. Frost, Vice-Chairman of the Central Price Regulation Committee, 30 June 1942.

(4) Gordon Russell, Designer’s Trade : An Autobiography, London, 1968, p.199.